« History is a damn dim candle over a damn dark abyss. » W. Stull Holt.

It is weird to say that this was an incredibly fascinating book and also a very boring book. Maybe boring is not the right word, maybe « too packed with information to be read easily » might be better.

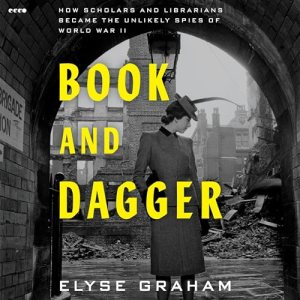

This very dense and information-packed book shows an incredible amount of research into « the ghosts » of World War II, that is, the people who helped the war effort but were completely invisible. We all know about the many men and women who worked at Bletchley Park to decode German messages. Elyse Graham researched at all the university professors and librarians who worked as spies for the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) in Germany, Sweden, Turkey, France, and many other countries. And by « university professors » I mean in particular people in the Humanities and Social Sciences: historians, psychologists, sociologists, economists, art historians, philosophers, etc.

These people could easily work alone, a lot less conspicuously than groups of soldiers, and find useful information for the war effort, for example by searching for old atlases, maps, and history books that would tell them about the less-travelled roads and railways the Germans might use to transport weapons or soldiers, or where they might hide an ammunition factory, for example, or look for newspapers published only in Germany and find key political information in them, all under the pretence of « academic research. » That work basically started what is today considered « intelligence, » and OSS became the foundation of the CIA.

The problem with this book is that there was SO MUCH important and fascinating information that I forgot almost everything. But I do remember that anthropologists before WWII were sometimes quite racist in the way they conducted their studies, and so much of their research was put to terrible uses during WWII (e.g., eugenics) that these abuses led the profession to change drastically after the war. Academia in general was deeply impacted, after the war, by the way these people worked, and that was super interesting for me to learn. The story of stolen art by the Nazis and how art historians were able to track some of it (and sometimes also steal it for themselves or their country under the pretence of « saving it ») was also very interesting. And a fun part of the book was about misinformation and how the Allies managed to influence the Germans with fake news, depressing songs and movies, and other tricks that psychologists knew would impact soldiers’ morale and decisions. (I talked about one of the most famous disinformation manoeuvres there, but there were thousands of them, including D-Day.) And of course, I never really understood what « intelligence » was, so now I understand much better all the different facets of what that word means in the military context.

The book’s conclusion brings up the very sad fact that most people today are no longer interested in studying the Humanities because we are told that a degree in literature, art history, philosophy, or history is useless in today’s economy. Sad world indeed.

Laissez un commentaire